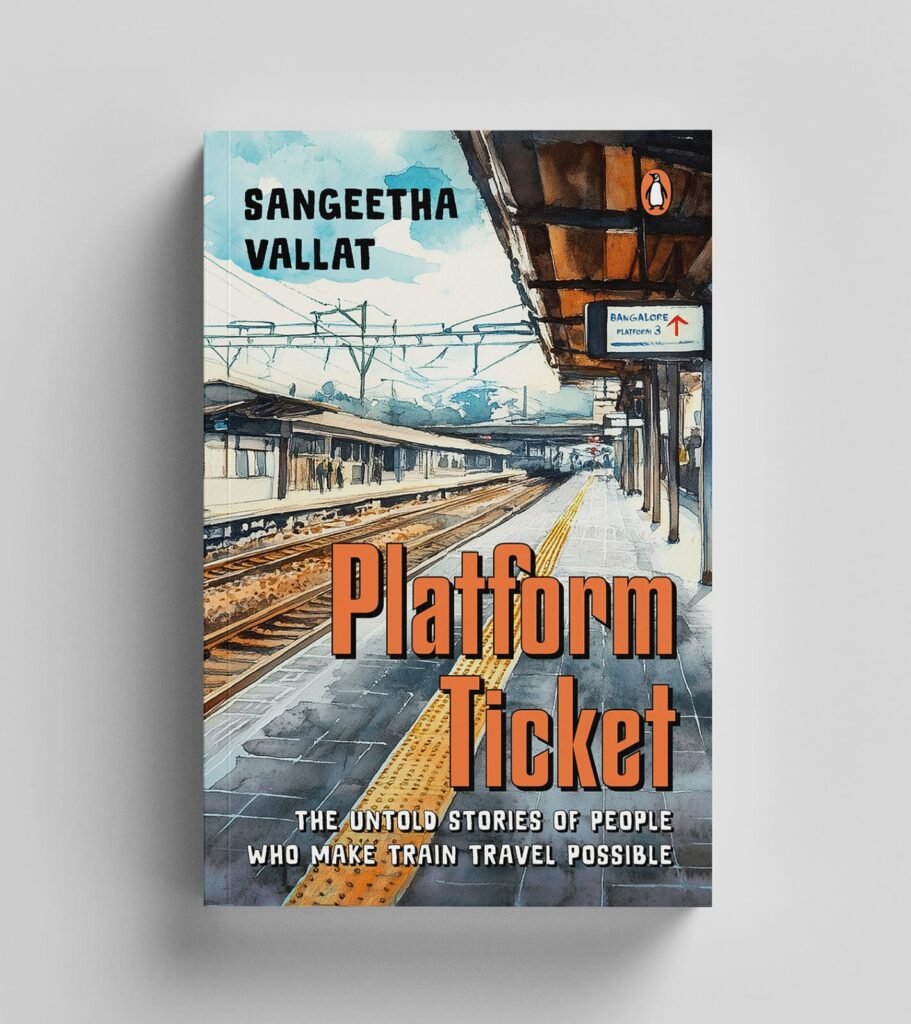

This story was published in the anthology collection ‘Existing Loudly Volume II’. The story combines my experiences of train travel with some everyday scenes at a railway platform, and a touch of fiction. You will find the actual version of this incident in my book Platform Ticket.

SILVER BRILLIANCE

The turbaned man, hunkered on the pavement opposite, was spreading his wares on a plastic sheet. He swished a yellow cloth like an angel waving her wand over the merchandise, forbidding the flecks of dust from listlessly settling on the heart-shaped keychains, multicoloured bead necklaces, or the trendy sunglasses. Asha watched him as she waited for the traffic lights to turn red, allowing her to cross over to the station. She envied him for the ease with which he conversed with his clients. His apparent contentment made her realise that happiness is self-achieved. A gaggle of young girls crowded around the preening vendor, elbowing each other for the knick-knacks.

Ah, the age of innocence. How blessed ignorance is! Asha thought as she passed the girls, still debating over the keychains. Asha bounded the twenty-eight steps leading to the platform, presuming them to symbolise one for every year of her life. The lights turned green, and the blare of the approaching train added to the chaos that engulfed her. She deftly dodged the peddlers who displayed their wares, hollering for business.

“Rs25 a dozen.” Screamed the fruit vendor.

“Fresh coriander and mint leaves! Amma buy a bunch, grind tasty chutney.” The old lady entreated the passers-by.

Beggars splayed their maimed bodies on the stairs, interspersing the vendors, and aspired to tingle the pedestrians’ altruistic behaviour by rattling their bowls.

“Ammmaaa… Saarr… God will shower his blessings on your family. Please drop some coins or currency notes.”

The urchins scratched their heads while nothing escaped the scrutiny of their eyes. They waited for the right opportunity.

A further stretch of 30 yards, Asha glided through the veritable bazaar of fragrances, absorbing strangers’ sweat and perfumes. Humanity failed to prevail as humans hurried unmindful of the hurt elbows or the stray hair that caught on to zippers of bags—each one rushing to outrun the others in the game of life. Asha then descended a few more steps, reached the platform to be swooped into the local train.

Heaving a sigh, she puckered her brows. The ladies compartment reeked of femininity. The glistening midriffs and the stained armpits nauseated her. Asha was pushed, poked, and jostled.

“Ouch! Are you blind? You broke my toe.” Yelled a bespectacled, stout woman.

“As if I intended to step on your toes. Why are you occupying so much space?” Barked a slender young girl.

“Oh! You have such a nasty mouth. I pity the guy who would marry you.”

“Do you have a son? Maybe I can marry him.”

The arguments escalated, and Asha steered clear of the loud-mouthed women and reached the back row. She smiled at the schoolgirl who would alight after a few stations. Rummaging in her bag, Asha picked and inserted the headphones. The melody, mixed with the trundling of the train, calmed her nerves. She closed her eyes and balanced her stance. In a while, the stench of the approaching bracken river broke her exaltation. The schoolgirl’s destination had arrived.

Asha rested her sore back and moaned in relief as she stuffed the headphones and glanced at the varied hues. Sarees, salwar, skirts, and jeans-clad women engaged in multifarious activity. A patter of numerous languages and accents spilled through as the women opened their tiffin boxes. The compartment stewed with diverse cuisines. Appetising aromas pervaded the cabin. From a corner wafted the deliciousness of succulent drumstick sambar and gingelly oil-drenched dosas, and on the other side, the pungency of garlic assailed the senses. Asha wrinkled her nostrils as someone relished dried fish curry. Tastes were approved, and women shared recipes.

Peddlers selling Roses and Jasmine thronged inside, and thankfully, the fragrance masked all the other odours. And soon after, almost every braid adorned a flower.

“Sister, buy a red rose. It will match your dress.” Marketed a dusky beauty.

Asha, though tempted to buy, restrained herself. She quickly estimated how many litres of milk a month could be purchased with the flower money these women splurged on without a care. She shook her head, and the girl’s eyes reflected empathy. The women engaged in discussions from menstruation to childbirth to episodes of quarrels with the mother-in-law, woes of the irresponsible teenagers, and despondency at drunk husbands. The countless conversations depicting the tedium of everyday existence dizzied Asha.

While the sea breeze played with her curls, Asha overheard the girl seated opposite on the phone.

“I couldn’t go to the reception. My parents were worried about how I would reach home so late. I am getting good marriage alliances, and they don’t want the neighbours to gossip or anything.”

The girl grinned at Asha and continued her rants, “I know I am still too young for marriage. It’s more to satisfy the wagging tongues of the many aunts in the family who are disgusted that my parents are letting me work instead of getting me married…. Hello, hello, can’t you hear me? Hello!”

She scratched behind her ears and said to no one in particular, “The line got cut. Poor signal.” An imperceptible smile crossed Asha’s lips, and ripples formed in the folds of her mind. A vision of her condoning aunts who practised speaking in overtones of reproval loomed largely. Last week, Asha had asserted her views and announced in clear terms that she would get married after her sisters completed their education. Being the eldest and the breadwinner in a family of women, she was burdened with responsibilities. Her poor mother trembled when her aunts visited, throwing insinuations.

“Are you married?” The question from the girl on the phone startled Asha.

“No.”

“You seem to be much older than me, yet unmarried. Why do my parents nag me!?”

Asha laughed, although annoyed, “All parents are in a hurry to marry off their daughters. It would be helpful if you could discuss your ambitions with them. They have your best interests at heart.”

Fortunately, the phone buzzed, and she left Asha to her musings.

Asha’s was the penultimate station, and the train was almost empty by then. She glanced around to check if the compartment was deserted. If it were, she would get down and change to the general compartment when the train halted. Asha preferred travelling the short distance to her destination in the general compartment to being alone in the ladies.

Her eyes were greeted by a passenger seated at the farthest corner. Asha shuddered and wasted a split second on the decision while the train dragged ahead. Clutching the bag to her chest, Asha gazed at the fleeting scenery while a sidelong glance registered the tall figure sauntering toward her.

“It is scary to sit alone, isn’t it?” Asked the hoarse voice, perched on the seat opposite, as she adjusted the parrot green sari that draped her body like a second skin.

Asha feigned nonchalance and surreptitiously observed the turmeric-stained face and the big red dot on the forehead.

“If you hadn’t been here, I would have shifted to the other compartment,” Continued the stranger, gesticulating like a dancer and stroking a square jaw.

Although the jingling bangles were mesmerising, Asha picked up her mobile and dialled a friend.

“This section hampers the mobile signal; you cannot make a call.” The familiarity of the stranger irked Asha.

When the train halted midway for an oncoming train, Asha’s countenance turned ashen.

“Don’t worry. The train will move soon. Drink water. You look pale.”

Then the stranger, with outstretched hands, touched Asha’s head, cracked her knuckles on her vermilion forehead, and then sashayed to the exit.

Asha whizzed to the foot over-bridge before the train screeched to a halt.

Asha’s stride faltered, and her eyes widened as she reached the top of the bridge. A day like any other, the regular train, the same platform, yet suddenly nothing was the same. A homeless man seated on the walkway had his hand underneath the tattered cloth covering his lower body. The hand jerked furiously. His eyes met Asha’s; he removed the cloth and flashed at her. His lecherous eyes stripped Asha. Not a squeak ensued from her parched throat. She couldn’t swallow her spit.

“Come, honey, come closer. I bet you haven’t seen anything like this before.” He said, slithering a pale tongue over his lips.

Her stomach was in knots, and her legs felt like jelly. Asha’s hands flailed in the air and clasped the railing. Bile soared inside Asha when a gust of wind delivered the fecund stench from the bedraggled man. She sensed footsteps behind her. The stranger from the train had followed her to the top of the stairs. The repulsion gave way to relief in Asha’s eyes. The stranger took charge of the situation and flung slippers at the homeless man.

“You swine! You filthy swine!”

The man tried to push but was no match for the heavy-set woman. Her single kick left him sprawled sideways.

Asha’s eyes flitted, and she cowered behind the angel.

The saviour screamed, “Help!” The patrolling Railway policeman and a few vendors from the platform rushed towards them, and the policeman apprehended the flasher. The clanging in Asha’s head grew louder. She baulked for a few moments, then followed her saviour to the police station at the platform’s end.

The women waited to register their complaint. Asha offered water to her new friend, Shilpa.

“Thank you. If you hadn’t come up the stairs….”

“Don’t think about that now. Relax.”

“Hmmm. I hope you are not in a hurry. Where do you work?”

“I don’t have a steady job now. Earlier, I worked in a software company. In our family, I was the only one who graduated and found a job. My parents were proud of me until I opted to live according to my terms.”

“Hmmm.” Asha inadvertently adjusted her dress and continued, “My aunts are pressurising me to get married. My working hours are not acceptable to the neighbourhood women. To shut them up, I need to settle down. We are expected to sacrifice our individuality for societal pressures.” Asha wondered at the ease with which she could open up to a stranger.

“If we opt to fight, we are ostracised.”

“Hmmm.”

“I see you every day. You work at the auditor’s firm, isn’t it?”

“Oh, yes. I have never seen you before today.”

“People do not like to see us. They turn their heads. Even you did not want to talk earlier.” A mischievous smile played on the betel-chewed lips.

“I am very sorry. I am ashamed of my behaviour. You come home; I will share my address. Meet my mother and sisters. They would be happy to meet you.”

Shilpa’s eyes crinkled, “It’s OK. I am used to such behaviour. Your family will not be happy to see me. The neighbourhood aunties would be busy creating stories.”

Asha lowered her eyes.

Soon, they were ushered to meet the officer in charge.

“What is your complaint?”

“Sir, that man misbehaved with her.”

“You stand aside.” The policeman snarled. Turning towards Asha, he asked, “Madam, you tell me, what happened?”

“That man was doing dirty things. He called me closer. Arrest him and put him in jail. Dirty scoundrel!”

“Relax, madam. Did you approach him anytime? Many passengers use the bridge. Why did he choose you?”

Asha crimsoned. “Why would I approach him? I don’t know anything. You beat and make him confess.”

“Madam, you need not teach us how to work. We know. Write your complaint. We will call you as a witness at any time. Will you come?”

Suddenly, the men sprang from their seats and saluted the officer who entered the office. The inquiry pattern shifted like a kaleidoscope, and Asha and Shilpa, who had been squirming just a few seconds ago, easily explained their issue.

The women completed the formalities at the railway police station and stepped out, concealing a sigh.

They bid farewell. Asha hesitated, wondering if she should share phone numbers. Then she checked her watch and rushed away, worrying about the pay cut she would incur for her late arrival.

They parted their ways as strangers again.

Asha scrambled out of the Railway station, and her eyes scanned the dimly lit corridor of the subway. A girl in a school uniform walked ahead, hugging her school bag, and her steps faltered when a group of boys approached, hooting and whistling. Asha paced forward, glaring at the boys. The young girl matched Asha’s strides.

Asha’s lips curled upwards as they emerged into the warmth of the silver brilliance.